![[David] Bronstein congratulates [Lubomir] Kavalek, Amsterdam 1968, a month before the protests in Czechoslovakia were stopped with military force by the Soviets. Photo: Dutch National Archives.](https://freight.cargo.site/t/original/i/409f7f1f1d654a86de11dd111773c308acd6b821aa67d4d777b299a07659d791/phpSq2aG4.png)

The Queen’s Gambit: chess as an ideological battleground

Jack Wareham

Online membership on chess websites exploded after the premiere of The Queen’s Gambit (2020), Netflix’s very dramatic and very serious miniseries about a young woman’s ascension through the ranks of international competitive chess.

The Queen’s Gambit has a plot, but do not pay too much attention to it. The story is propelled by the “she-showed-him-didn’t-she” montage:

1: Male chess player, doubtful.

2: His opponent, Beth Harmon (played by Anya Taylor-Joy in a loose approximation of Bobby Fischer, eccentric chess prodigy turned 20th century world champion), determined.

3: Montage of chess game – Harmon quickly winning.

4: Man, grimacing and generally looking emasculated and upset.

5: Harmon, smirking.

Attentive and obsessive Netflixers will notice the resemblance between this sequence, repeated at least once an episode, and similar storylines from Emily in Paris, in which the sticktoitive protagonist embarrasses the pretentious business boys with her marketing genius. The Queen’s Gambit is ambient television meets all-American pop feminism, and yours truly watched every minute of it – notwithstanding its restaging of worn-out Cold War drama.

![]()

Harmon is plucked out of an orphanage as a teenager, already a chess savant from sneaking games in the boiler room with janitor Mr. Shaibel, the surly old grump who begrudgingly shows her the ropes. She spends the next decade in a trank-induced haze, visualizing chess games on the ceiling, until she is adopted by a boozy foster mom. (N.b. This character has the class position of a Midwestern housewife, the diction of a British grand bourgeois, and the postured elegance of a veritable Southern belle.)

Harmon starts winning more and more and eventually sets her crosshairs on Vasily Borgov, the sullen, bureaucratic Soviet champion. The whole thing is a neat little Cold War metaphor – Harmon, the brazen, fabulous attacker set against Borgov, the robotic, defensive communist who probably worships Brutalist architecture and wool coats. Harmon is abstract expressionism; Borgov is socialist realism. It’s loosely based on the 1972 world championship match between Bobby Fischer and Boris Spassky, in which Fischer stormed out after game ten, perhaps because he needed to devote more time to thinking about how much he hated Jews.

(See also: Tobey Maguire plays Bobby Fischer in Pawn Sacrifice, a movie with a title so on-the-nose it makes you wince. The true extent of the US government’s involvement in Fischer’s chess career is unknown, but “Nobel Peace Prize recipient” Henry Kissinger did give him a phone call before his Spassky match – large portions of the transcript are redacted.)

Discourse about chess history is usually structured around a dialectic between the passive robot (who plays quietly and accurately) and the bold romantic (who sacrifices queens willy nilly and considers themselves an artist or something). Before chess became a proxy battle for the Cold War, the Soviets were universally viewed as the most exciting chessers in the world, an ethos aligned with the revolutionary dynamism of the Bolsheviks.

But, in the world of The Queen’s Gambit, the Soviet players are scientific and precise. They lack the American individualist spunk exemplified by Harmon’s friend Benny Watts, a fellow chess master who inexplicably dons a leather jacket and a cowboy hat in nearly every scene. One is reminded of Bobby Fischer’s attempt to become the most elegant man in the world, a goal for which he purchased seventeen hand-tailored suits. (Chess has always been haunted by the irritating aesthetic of the “gentleman”, with his twisty mustaches and verbose language.)

Why is chess such a battleground for ideological politics? Probably because of the misguided belief that chess masters are smart in any meaningful sense beyond calculating and memorizing variations. To disprove the link between chess mastery and intelligence, one should look no further than current world champ Magnus Carlsen, a dolt from Norway who signaled his support for Donald Trump’s 2016 election win by playing the uncommon Trompowsky Attack the next week in a high-level match.

![]()

Putting this aside, we should engage The Queen’s Gambit on its own terms – as a trendy historical retelling that inserts a successful woman into a historically male space. Harmon is able to wow the boys with her innate talent, causing them to overcome their initial misogyny. Here, however, we must pause again, because in reality she would have faced barriers much more overt and grotesque.

Grandmaster Judit Polgar has decried The Queen’s Gambit for its drastic minimization of the sexism that femmes face in chess. (Interestingly, Polgar and her two sisters were trained by their father, László, a psychologist who wanted to prove that “geniuses are made, not born.” All three children became chess masters, suggesting that the gender disparity in chess is at least partially the result of parents not rewarding girls for analytical thinking from a young age.) When International Master Anna Rudolf beat a series of male grandmasters in 2008, she was accused of hiding a microchip in… you guessed it, her lip-balm.

The Queen’s Gambit succumbs to the seductive logic of “Lean In” girlbossery, a kind of cheapened feminism in which sexism is refuted by talent, instead of combatted with the cultivation of political power. (Compare this with Amelia Horgan’s piece in Jacobin, which eviscerates the misguided notion that feminism means prioritizing, for example, a female president over the material demands of universal childcare, abortion rights, etc.)

By the end of The Queen’s Gambit, the impossibly-chic-for-a-chess-player Beth Harmon wins it all. But what have we gained from rewriting history to be woke? The impulse to transherstorically remold the past in the image of the present is at best a distraction from the project of materialist politics, and at worst a subtle but insidious justification for American hegemony. In the final analysis, The Queen’s Gambit restores the reactionary nostalgia that feminists have worked hard to dismantle. To make matters worse, it’s gussied up with a faux-noir aesthetic that can best be described as David Fincher reading Gloria Steinem.

The Queen’s Gambit has a plot, but do not pay too much attention to it. The story is propelled by the “she-showed-him-didn’t-she” montage:

1: Male chess player, doubtful.

2: His opponent, Beth Harmon (played by Anya Taylor-Joy in a loose approximation of Bobby Fischer, eccentric chess prodigy turned 20th century world champion), determined.

3: Montage of chess game – Harmon quickly winning.

4: Man, grimacing and generally looking emasculated and upset.

5: Harmon, smirking.

Attentive and obsessive Netflixers will notice the resemblance between this sequence, repeated at least once an episode, and similar storylines from Emily in Paris, in which the sticktoitive protagonist embarrasses the pretentious business boys with her marketing genius. The Queen’s Gambit is ambient television meets all-American pop feminism, and yours truly watched every minute of it – notwithstanding its restaging of worn-out Cold War drama.

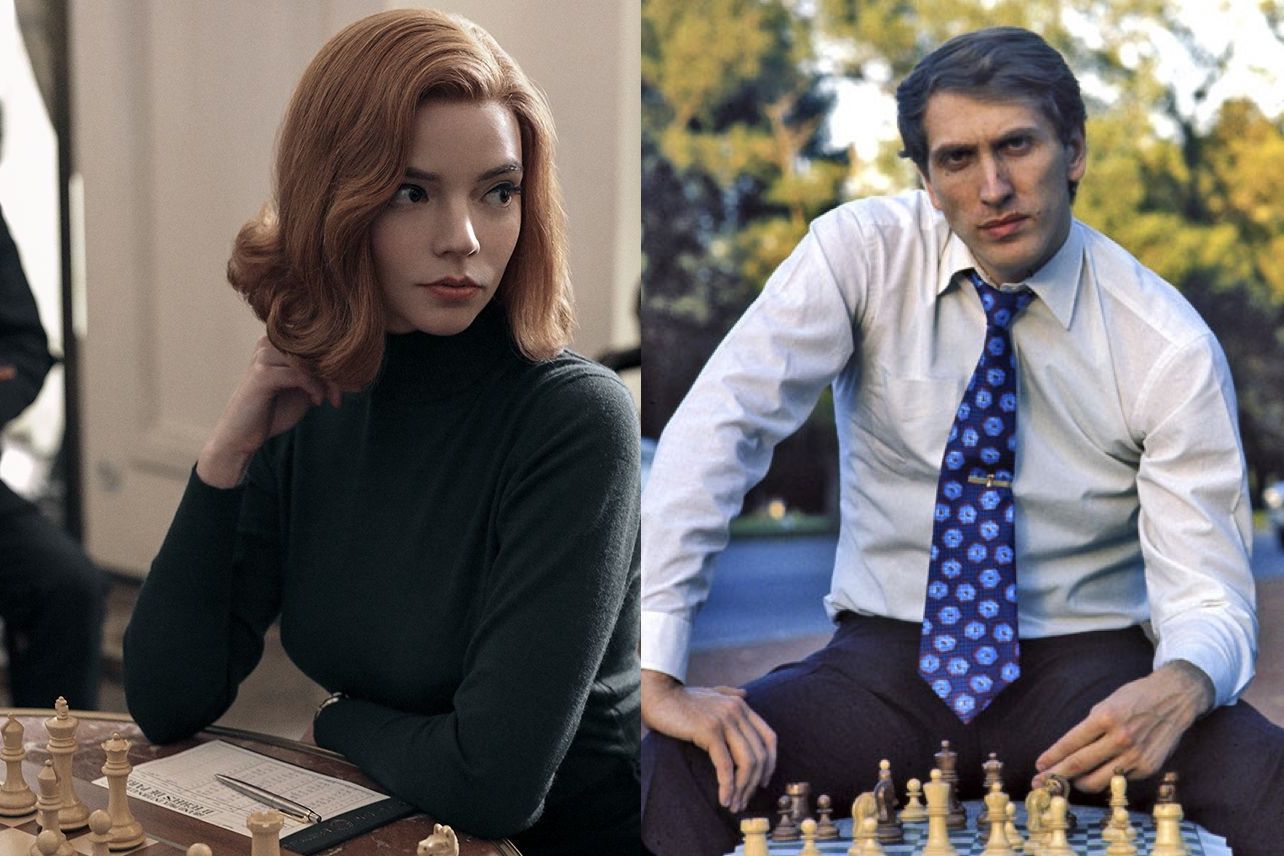

Left, Anya Taylor-Joy as Beth Harmon and right, Bobby Fischer photographed by Harry Benson in approximately 1972.

Harmon is plucked out of an orphanage as a teenager, already a chess savant from sneaking games in the boiler room with janitor Mr. Shaibel, the surly old grump who begrudgingly shows her the ropes. She spends the next decade in a trank-induced haze, visualizing chess games on the ceiling, until she is adopted by a boozy foster mom. (N.b. This character has the class position of a Midwestern housewife, the diction of a British grand bourgeois, and the postured elegance of a veritable Southern belle.)

Harmon starts winning more and more and eventually sets her crosshairs on Vasily Borgov, the sullen, bureaucratic Soviet champion. The whole thing is a neat little Cold War metaphor – Harmon, the brazen, fabulous attacker set against Borgov, the robotic, defensive communist who probably worships Brutalist architecture and wool coats. Harmon is abstract expressionism; Borgov is socialist realism. It’s loosely based on the 1972 world championship match between Bobby Fischer and Boris Spassky, in which Fischer stormed out after game ten, perhaps because he needed to devote more time to thinking about how much he hated Jews.

(See also: Tobey Maguire plays Bobby Fischer in Pawn Sacrifice, a movie with a title so on-the-nose it makes you wince. The true extent of the US government’s involvement in Fischer’s chess career is unknown, but “Nobel Peace Prize recipient” Henry Kissinger did give him a phone call before his Spassky match – large portions of the transcript are redacted.)

Discourse about chess history is usually structured around a dialectic between the passive robot (who plays quietly and accurately) and the bold romantic (who sacrifices queens willy nilly and considers themselves an artist or something). Before chess became a proxy battle for the Cold War, the Soviets were universally viewed as the most exciting chessers in the world, an ethos aligned with the revolutionary dynamism of the Bolsheviks.

But, in the world of The Queen’s Gambit, the Soviet players are scientific and precise. They lack the American individualist spunk exemplified by Harmon’s friend Benny Watts, a fellow chess master who inexplicably dons a leather jacket and a cowboy hat in nearly every scene. One is reminded of Bobby Fischer’s attempt to become the most elegant man in the world, a goal for which he purchased seventeen hand-tailored suits. (Chess has always been haunted by the irritating aesthetic of the “gentleman”, with his twisty mustaches and verbose language.)

Why is chess such a battleground for ideological politics? Probably because of the misguided belief that chess masters are smart in any meaningful sense beyond calculating and memorizing variations. To disprove the link between chess mastery and intelligence, one should look no further than current world champ Magnus Carlsen, a dolt from Norway who signaled his support for Donald Trump’s 2016 election win by playing the uncommon Trompowsky Attack the next week in a high-level match.

Thomas Brodie-Sangster as Benny Watts, looking characteristically cringe.

Putting this aside, we should engage The Queen’s Gambit on its own terms – as a trendy historical retelling that inserts a successful woman into a historically male space. Harmon is able to wow the boys with her innate talent, causing them to overcome their initial misogyny. Here, however, we must pause again, because in reality she would have faced barriers much more overt and grotesque.

Grandmaster Judit Polgar has decried The Queen’s Gambit for its drastic minimization of the sexism that femmes face in chess. (Interestingly, Polgar and her two sisters were trained by their father, László, a psychologist who wanted to prove that “geniuses are made, not born.” All three children became chess masters, suggesting that the gender disparity in chess is at least partially the result of parents not rewarding girls for analytical thinking from a young age.) When International Master Anna Rudolf beat a series of male grandmasters in 2008, she was accused of hiding a microchip in… you guessed it, her lip-balm.

The Queen’s Gambit succumbs to the seductive logic of “Lean In” girlbossery, a kind of cheapened feminism in which sexism is refuted by talent, instead of combatted with the cultivation of political power. (Compare this with Amelia Horgan’s piece in Jacobin, which eviscerates the misguided notion that feminism means prioritizing, for example, a female president over the material demands of universal childcare, abortion rights, etc.)

By the end of The Queen’s Gambit, the impossibly-chic-for-a-chess-player Beth Harmon wins it all. But what have we gained from rewriting history to be woke? The impulse to transherstorically remold the past in the image of the present is at best a distraction from the project of materialist politics, and at worst a subtle but insidious justification for American hegemony. In the final analysis, The Queen’s Gambit restores the reactionary nostalgia that feminists have worked hard to dismantle. To make matters worse, it’s gussied up with a faux-noir aesthetic that can best be described as David Fincher reading Gloria Steinem.